(published earlier in: Business Standard, October 11, 2010)

[by] Paranjoy Guha Thakurta

The disclaimer is deceptive. “This is a work of fiction,” it reads, adding with predictable monotony: “Names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and any resemblance to any actual person, living or dead, events or locales is entirely coincidental.” How disappointing? How exhilarating? Right through its 337 pages, one was left wondering where the distinction had been drawn between fact and fiction, where the hiatus between perception and reality had been blurred.

This is a novel about the Roaring Sixties around a clutch of upper-class students, most of them from Delhi’s famous Mission College — Pranav, Mohan, Rathin, Sin Taw, Divya, Shipra — who are fired with revolutionary ardour to de-class themselves and change the country (and the world) they lived in, if necessary, through violent means. This was a tumultuous time when Naxalbari, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Bob Dylan, Jim Morrison and the Mahabharata mingled in their minds seamlessly long before globalisation, as we know it today, became fashionable — it was then called “internationalism”.

As the characters encounter “people unlike us” in the farms and fields of Bharat, and in the stinking slums of the urban underprivileged, they get intimately involved in a series of intricate encounters that range from the banal to the biological and the blasphemous. The intellectuals interact with individuals who turn out to be very different from their archetypes, theoretically constructed amid animated discussions on Marxism, Maoism and the state of the universe, not to mention debates on whether or not China and/or the erstwhile Soviet Union should be classified as “state-capitalist” or as a “degenerate workers’ state”. Though the main characters inhabit worlds of fantasy, their feet appear firmly placed on slush, paradoxically, especially in their association with aam admi and auratey.

Those on the other side include Hardip, the large-hearted truck driver, Jehur, the enlightened worker who is accidentally killed, Lata, the lovable prostitute, Sardul Singh, the apology of a kulak, not to mention, the ganja-smoking hippies from France and the cross-country cyclist from Japan. The teacher Oroon-da, the thinker Abani-kaka, the guitar-strumming Bob — form important links in the book’s underlying discourse on violence, societal change and how dictatorial processes and chauvinistic values tend to replicate themselves in different contexts. The issues that are discussed invariably revolve around the dialectics of revolution and the viability of violently overthrowing the establishment.

The journeys by the students who aspire to become agents of change are predictably portrayed. This is equally true of the way in which the policemen have been depicted. From the lowly constables to the commissioners (with or without a conscience), the cops are sharply etched, for they become an important counterfoil to the protagonists who grapple not only with indignation at the poverty and injustice they see around them but also with more mundane issues such as sex and shitting.

The excerpts from the songs are in English and Hindi, usually not translated or footnoted. But the expletives are explained, on occasion in excruciating detail. In terms of style, the publication is pure “mockumentary”, complete with portions from the so-called archival papers that appear to document the denouement of people helplessly caught in a vortex of violence as dramatic historical events unfold around them. The author uses cinematic patterns of juxtaposing a series of stories traversing space, time and subcontinent that come together, fall apart, jumble up and then — amazingly — become coherent all over again. The use of the flash-forward technique is, however, used rather sparingly. And one is not going to play party-pooper here by revealing the surprising twists in the tail of the tale.

The Dilip Simeon in the bland blurb of the book is unusually reticent in his new avatar. We are informed that he studied in the University of Delhi in the late-1960s, that he taught there till 1994, that his publications include a monograph on labour history, academic essays, short stories and articles on contemporary politics. We are further told that the author lives in Delhi in spite of his avid interest not only in books and music but also in birds, mountains and the sea.

Not a word about his involvement in left-wing politics needs explicit mention here, nor a sentence about his disillusionment with extreme-left ideologies, for all that becomes amply evident in his writing about the late-1960s. Four decades later, as a third of the geographical area of India is classified as a red corridor stretching from the Himalayas to the Bay of Bengal — the nation’s biggest internal security threat, says the prime minister ad nauseam — Simeon’s book resonates with relevance that is contemporary.

At this juncture, a few personal observations are needed. This reviewer knows the author and has known of him for some decades now. His colonel father headed the school where I studied and which has been in the news of late for the wrong reasons. We were in same college and university. Having spent nearly half my life in my city of birth, Kolkata — sorry sister, it used to be called Calcutta those days — it was a memorable and nostalgic roller-coaster trip around an urban agglomeration where considerable portions of the book are situated. It’s a first novel and a brilliant one at that, one has no hesitation stating. I, for one, found it difficult to put down. But then I am guilty of bias.

The reviewer is an independent journalist and an educator. His work experience, spanning over 33 years, cuts across different media: print, radio, television and documentary cinema

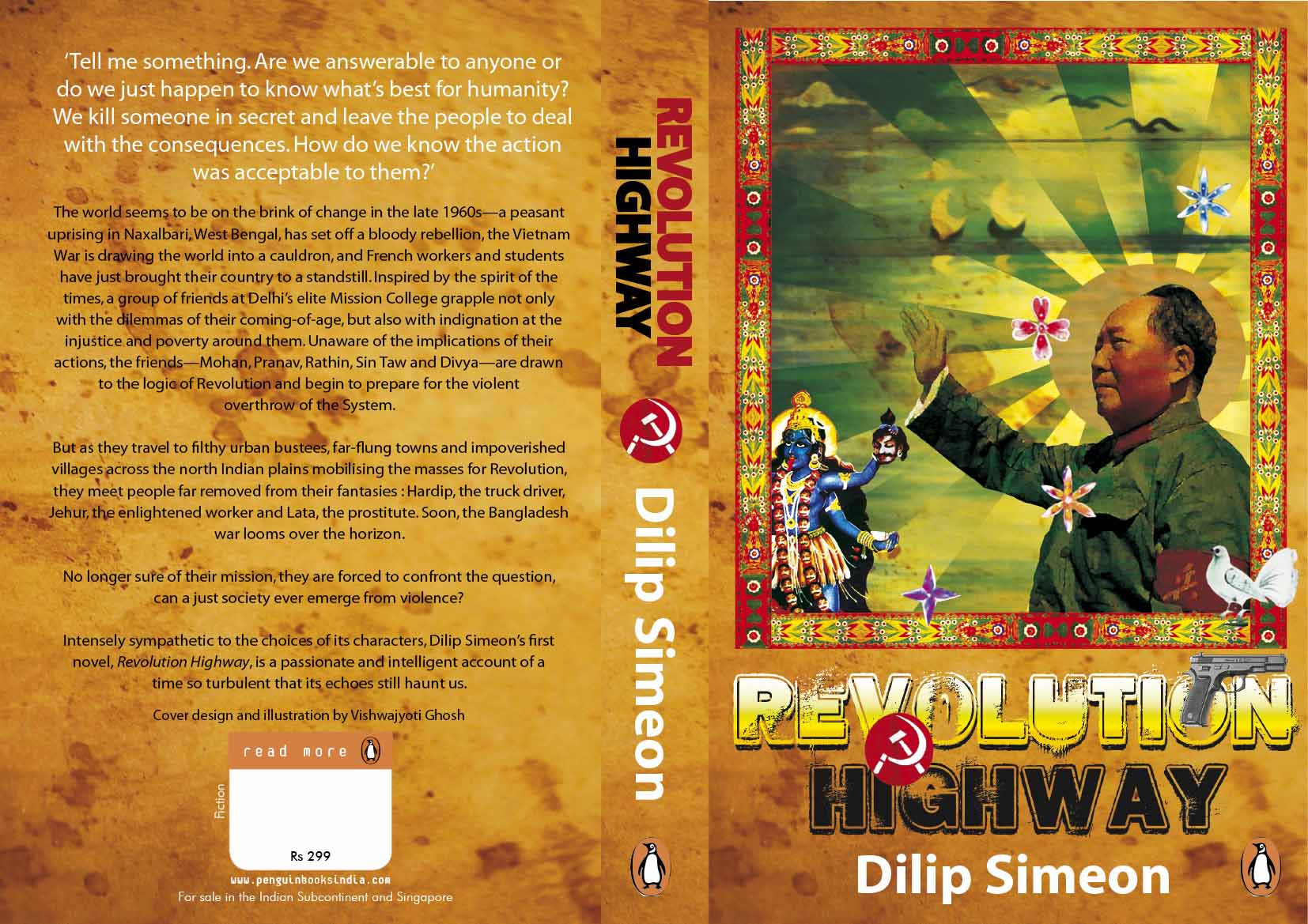

REVOLUTION HIGHWAY

Dilip Simeon

Penguin Books India, 2010

337 pages; Rs 299

Posted on October 16, 2010

0